Dearest Dorothy, Who Would Have Ever Thought?!*

(*From Charlene Baumbich’s book of the same title)

My story begins on a high note, the 1960s, during the time I was an undergraduate student. Higher education was on a roll. Enrollments were booming, campuses were expanding, a number of institutions had transitioned from college to university, and community colleges were being established across the country.

My story begins on a high note, the 1960s, during the time I was an undergraduate student. Higher education was on a roll. Enrollments were booming, campuses were expanding, a number of institutions had transitioned from college to university, and community colleges were being established across the country.

It was higher education’s Golden Era, the “go-go” years.

That Golden Era has turned into the Turbulent Era.

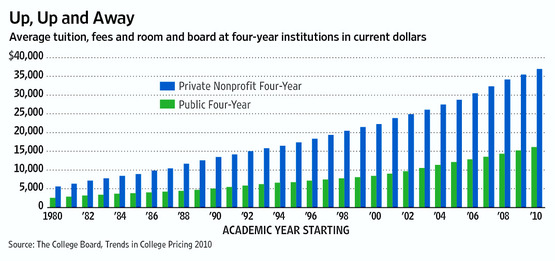

While higher education continues to do many and important things, issues and problems abound—and in ways I could never have imagined back then. Tuition has increased over 1200% over the past 30 years. Aggregate student debt has surpassed $1 trillion dollars nationally. And, day after day, news headlines call attention to an array of onerous issues, things like campus sexual assaults, racist and sexualized fraternities, outsized college athletics, administrative bloat, and unfair treatment of part-time and adjunct teaching faculty. Circumstances have led to activism, government intervention, and plain old head-shaking (e.g., Yale spending nearly $500 million last year in endowment management fees—3x the amount of endowment dollars spent on university programs).

What happened to higher education? To answer, let me begin by looking at what I believe higher education to be. Then I’ll comment on what I believe has precipitated the troubles.

Social institutions serve the public good by performing one or more vital social functions—activities deemed essential for society’s welfare.

Higher education as social institution and business

At its core, I believe higher education is a social institution. Social institutions serve the public good by performing one or more vital social functions—activities deemed essential for society’s welfare. One way higher education fulfills that responsibility is by making college affordable. It’s not in society’s best interests for a college education to be a private good, available only to those who can afford it.

But higher education isn’t a social institution only. It’s a business, too. Schools have to manage and optimize business outcomes. And colleges and universities operate in a highly competitive environment. There are many schools, not a few, and institutions work deliberately to accentuate distinctiveness. “Branding” is the rage.

So, from my vantage point, higher education is a hybrid—social institution and business both. Balance comes by way of valuing and paying attention to each dimension, forging connections, and stimulating synergies—all for the purpose of fulfilling social responsibilities in a business-wise manner.

The problem today—as I see it—is that higher education is out-of-balance. There’s too much emphasis on the business side of higher education and insufficient attention being given to higher education as a social institution.

But let’s face it: there is a lot of pressure on higher education these days “to deliver,” especially public higher education. Some states have systems in place to measure and compare public institutions—with state allocations hanging in the balance. Metrics tend to focus on measuring inputs (e.g., academic standing of incoming freshmen), throughputs (e.g., average time-to-degree), and outputs/outcomes (e.g., % of graduates employed full-time in their fields of study). Performance makes the difference in being judged good, better, and best—or less.

But the problem, as I see it, is that the predominantly used measurement systems crowd out other ways of evaluating higher education.

It’s good for the public to have access to information of that kind, and it’s important for higher education’s administrators to be accountable. But the problem, as I see it, is that the predominantly used measurement systems crowd out other ways of evaluating higher education.

What’s missing?

It’s evaluating higher education’s performance as a social institution. Here are four ways. Higher education should be evaluated on ways it makes the world a better place—reducing poverty, feeding the world, improving human health, and the like. Higher education should be evaluated on how well it develops students’ capacity to understand issues facing the world. Higher education should be evaluated on how well it develops students’ capacity to participate as informed and engaged citizens. And higher education should be evaluated on how well it functions as a model social institution (e.g., increasing faculty and student diversity, compensating part-time and adjunct faculty fairly, having open discussions about institutional priorities and directions).

It’s not as though none of this is happening on America’s campuses today. It’s just not happening as often or as extensively as it could. Why? It’s not fundamental to the prevailing paradigm associated with collegiate leadership and management.

Money, prestige, and winning

What’s happening instead? Administrative leaders–including boards that govern our colleges and universities—focus on other matters, three in particular: money (raising it), prestige (getting it), and winning (securing it). Battles between schools aren’t taking place just on athletic fields these days; they’re being fought over just about everything in higher education—students, faculty, funding, and donor dollars. Positioning is key. Advancing the brand predominates. And a “one-size-fits-all” model prevails—the research university as coin of the realm.

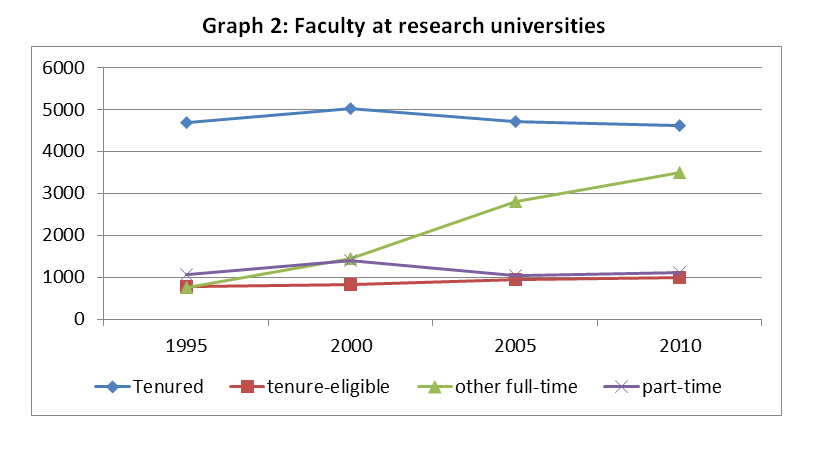

Doing all of that requires administrative person-power. And an earmark of today’s higher education is the large number of people engaged in its administration. In the “The Administered University” 10 times more administrators than faculty members were hired over a 15-year span. Included in the administrative sea change is the number of support staff members working in collegiate marketing, communications, fund raising, and branding.

Without question, higher education spends a lot of time, money, and attention advancing itself.

How did higher education get this way? There are multiple reasons.

And while I’d love to start by blaming state legislatures for funding cuts, doing so would take higher education off the hook.

And while I’d love to start by blaming state legislatures for funding cuts, doing so would take higher education off the hook.

An alternative explanation is that higher education is just about where you’d expect it to be—given the prevailing approach to institutional leadership and management. That sounds like an indictment, but it’s not. It acknowledges an approach that values getting big hits and scoring big plays.

I believe there was a tipping point—I sense that it came somewhere in the 1990s — when higher education’s administrative paradigm shifted. Before then, there seemed to be more administrative emphasis on “the work”—on scholarship as expressed through teaching, research, and service, and on students and their development. Many executive administrators—a lion’s share of whom were promoted into positions because they were outstanding scholars—seemed to view themselves more as custodians of the Academy and less as business executives. These days it feels just the opposite.

One can argue that higher education was forced into the prevailing approach because it has had to fend for itself. And that argument holds water, too. Public higher education has become a target of political ire—especially of politically conservative governors who want higher education to move in directions they prefer. The story unfolding in Wisconsin is especially notable: a high-profile governor is imposing major budget cuts on the state university system, redefining tenure, and devolving the influence of academic governance. Academic fields that aren’t perceived to be job-producing and income-lucrative are under scrutiny — the humanities and social sciences, especially. Some believe those fields “don’t serve the job market adequately.” Consider Florida Gov. Rick Scott’s infamous reference: “We don’t need a lot more anthropologists in our state.”

I used to know what it meant to use the words “college” and “college education,” but today I don’t.

But there’s more to it. Higher education’s response over the years has changed the basic character of the sector. How so?

I used to know what it meant to use the words “college” and “college education,” but today I don’t. These days, “colleges” offer an array of degrees, all in conjunction with a seemingly common frame of reference, “a college education.” But it’s really an apples and oranges environment. For example, Florida technical schools recently transitioned to collegiate status. Why? It’s about public relations. To quote a lead administrator: “When people see the word ‘college’ it draws more candidates because they think of post-secondary opportunities and make inquiries.” Dean Alice-in-Wonderful couldn’t have said it better.

Why is this happening? One answer is this: higher education changed in response to the massive scale-up demanded after World War II. The good thing: more Americans had more opportunities to enter higher education and complete degrees. But what were they getting? The answer has provoked consumers of higher education to be careful and strategic when making college choices.

Consider the argument in Is College Worth It?, a book written by William Bennett, former U.S. Secretary of Education, and David Willezol. The co-authors contend that only about 150 U.S. colleges and universities are “worth attending”—a mix of high-status schools (e.g., Cornell) and institutions with science and engineering foci (e.g., Purdue). If students can’t matriculate at one of those places, then they should study in-demand fields at lower-ranked schools—matriculating in the STEM disciplines, preferably—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. What’s the downside of not following that advice? The authors assert that graduates are likely to be less marketable and may end up accumulating sizeable college debt.

What a stark contrast to the time I went to college! I didn’t give much thought to job, career, and income. I believed all would come, in time. For me, the purpose of college was to learn and mature—as a person and professional.

Today that’s the minority opinion among college goers, but expectations associated with obtaining a college degree haven’t changed much over the years. A college degree—then and now—is “a ticket,” a pathway to a good (and better) life with better job opportunities, more career advancement possibilities, and significantly more income earned over a lifetime. There’s truth in those perceptions, too: the data show it.

What has changed? Society did.

Toward a neoliberal society . . . and higher education

In the 1930’s Franklin Delano Roosevelt had a tremendous influence on American society by how he responded to the economic crisis caused by The Great Depression (e.g., establishing the Social Security system). In the 1960s Lyndon Baines Johnson had a tremendous influence on American society by how he responded to widespread calls for social change (e.g., The Voting Rights Act of 1965). And, in the 1980s, Ronald Reagan had a tremendous influence on American society by re-scripting America’s economic and social order.

Reagan choreographed a sea change in political, social, and economic life. It was a shift away from Progressivism, which had prevailed during the previous 50 years.

Reagan lowered tax rates for the wealthy, deregulated corporate America, criticized “big” government as inefficient and often wasteful, and anointed the nonprofit sector as a major vehicle for social programs.

Dubbed “The Reagan Revolution,” Reagan choreographed a sea change in political, social, and economic life. It was a shift away from Progressivism, which had prevailed during the previous 50 years. Plutocrats had more influence. The role of government changed. The private sector operated less encumbered. And self-interest prevailed over welfare of the collective.

All of this took root in America, grew, and persists to this day. It’s a widespread and embedded social philosophy called Neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism’s major tenets include beliefs that “the market” predominates; public expenditures for social services should be cut; government regulations should be reduced; government-controlled services should be privatized; and “the public good” and “community” are outdated concepts. The individual rules instead (a notion well reflected in the 2012 refrain, “We built that!”)

Neoliberalism extends the logic of financial market into literally all aspects of social life. Individuals and institutions become commodities in “social markets” with money-related metrics used to evaluate value and success. It happens, for example, when the value a college degree is evaluated singularly as a return-on-investment as does the PayScale evaluation system.

The New York Times essayist David Brooks believes that mindset induces a focus on self. While “it’s natural that many people would organize their lives in utilitarian and consequentialist terms,” Brooks writes, “it’s possible to get carried away,” because “human life is not just a means to produce outcomes.”

An argument can also be made that a neoliberal ethic has infected America’s institutions. Many organizations have become self-absorbed—hyper-focused on internal matters, lathered with self-promotion.

But there’s more. An argument can be made that a neoliberal ethic has infected America’s institutions. Many organizations have become self-absorbed—hyper-focused on internal matters, lathered with self-promotion. The consequences often serve to erode public trust. Examples include corporate inversion (a tax-dodging strategy) and insular responses to violations of the public trust. John Creighton and Richard Harwood found that an inward-facing tilt—a “what’s best for the organization” orientation—exists across the country. The co-authors gave it a name: “The Organization-First Approach.

The conclusion to which I’ve come is that neoliberalism has become a dominant social philosophy in this country. And while I don’t think it happened overnight, I also believe –that over time—neoliberalism has become a prevailing ethic in American higher education. Higher education today, I believe, is a largely neoliberal institution.

How did I come to think that way? Outside of neoliberalism I’ve not found an interpretative perspective that explains what I’ve observed and experienced over the past twenty years. See, for example, Ronald Barnett’s “The Entrepreneurial University” in Imagining the University; Daniel Saunders’ extensive analysis in “Neoliberal Ideology and Public Higher Education in the United States”; William Deresiewicz’s soulful essay, “The Neoliberal Arts”; and Henry Giroux’s forceful critique in Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education.

I’ve also come to understand how hard it will be to counter a neoliberal ethic. That’s because “the neoliberal way” has become commonplace. Analyst Jason Hickel puts it well: neoliberalism is “the common-sense furniture of everyday life.” To critique neoliberalism, then, is to find fault with normality.

I’ve found myself falling into that very trap. For example, just the other day I read a newspaper article about a friend who recently assumed the presidency of a regional university in my home state. It’s a relatively new, second-tier, school that has struggled with identity and direction. My friend, who’s engaged in a major institutional turnabout, was lauded by the newspaper reporter for his strong and bold leadership. My first reaction was to feel really pleased for my colleague. But, then, I also reminded myself of what he was doing: “strong and bold leadership” = a neoliberal approach to higher education—the very approach I protest in this essay.

Combatting neoliberalism in higher education

That shows it’s not easy raising questions and finding fault with something that represents a taken-for-granted way of doing business. Consider how Margaret Thatcher interpreted neoliberalism back in the ‘80s: “there is no other alternative” (TINA). Accepted uncritically it’s the only way.

Cracks in neoliberalism are showing. We’re experiencing the dysfunctional consequences of a neoliberal ethic, problematic outcomes that are raising questions, drawing concern, and getting peoples’ attention.

Well, perhaps it isn’t. Cracks in neoliberalism are showing. We’re experiencing the dysfunctional consequences of a neoliberal ethic, problematic outcomes that are raising questions, drawing concern, and getting peoples’ attention. In higher education it’s cost and debt, among other issues. None of it “seems right” and that perception leads to raising questions and looking for answers. Why is this happening? What can be done? Uncritical acceptance could, and hopefully will, lead to a search for alternatives.

What can you and I do? Creating awareness is the first step in any change effort. I have a simple three-step recipe for that. First, name it, i.e., name neoliberalism for what it is. Second, disdain it, i.e., disdain neoliberalism for what it does. And, third, proclaim it, i.e., offer reasonable and practical alternatives to counter/replace neoliberalism’s hold.

What’s my response? As presented earlier in this essay I believe it’s a matter of finding balance—correcting an imbalance that I perceive in higher education today.

A well-known assertion is, “We need to run this place like a business!” That assertion meshes well with understanding higher education as business. But there’s a companion question, too: “What business are we in?” That question gets at higher education as social institution.

Balance between higher education as business and higher education as social institution comes when the assertion and the question are considered equally and acted on simultaneously.

Approaching higher education that way represents a both-and outcome: it befits higher education’s historic underpinnings as social institution and enhances its viability in today’s competitive world.

It also enables posing loftier questions

- What’s the purpose of higher education?

- What’s a college/university education for?

and seeking answers that are in the public good.

If we don’t take an approach like that, then things will probably stay the same or get worse. The cost is steep: higher education’s soul.

Those who are concerned about higher education need to become part of change. It’s not enough for you to speak out. You need to act up, too. Take action in your classrooms, in your research, in your service, and in your department, school, and committee work. You don’t have to start big. Just do something.

And seek out others who feel similarly. Organize with them and develop a shared commitment to act together. Then see things through. An example of my efforts (with colleagues) is presented here.

Yes, Dearest Dorothy, who would have ever thought?! I didn’t. I naively thought that the higher education I came to know—lo, those many years ago—would stay the same. Higher education would always be a shining example of a social institution par excellence.

I wanted to be a part of it. That’s why I came. That’s why I stayed. Then it changed.

Let’s do something about that.

—————————————-

Many of the ideas in this essay were drawn from work that appeared previously in LA Progressive.

—————————————-

Frank A. Fear is professor emeritus, Michigan State University, where he worked as faculty member and administrator from 1978-2012. Frank is primarily interested in the connection between public and nonprofit institutions and the public good. Frank writes a weekly column on sports and society for The Sports Column in Baltimore, Maryland, where he also serves as operations manager. He writes about social issues for the Los Angeles-based LA Progressive.

Frank A. Fear is professor emeritus, Michigan State University, where he worked as faculty member and administrator from 1978-2012. Frank is primarily interested in the connection between public and nonprofit institutions and the public good. Frank writes a weekly column on sports and society for The Sports Column in Baltimore, Maryland, where he also serves as operations manager. He writes about social issues for the Los Angeles-based LA Progressive.

Such A Great Blog. Thank U For Sharing Useful Information About Neoliberalism Comes to Higher Education. This Article Really Amzing And So Much Helpful For Me. Keep It Up:).