In his book about HBCU founders, Samuel H. Johnson aims to educate and inspire today’s generation of young people.

The headshaking realities associated with today’s higher education give me pause for thought. I need to be reminded of and inspired by what higher education used to be, including what it was founded to be. That is where Samuel H. Johnson’s children’s book fills the bill.

Center for Education Research Applicants, 2022, and available for purchase at Amazon.com

Entitled HBCUs The Living Legacies: Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Johnson offers seventeen vignettes of how HBCUs were founded—by whom and why—designed to expose young people to the times, places, and people that transformed American higher education.

Told in storybook fashion, Johnson’s rendition is engaging and informative. It is about a group of trailblazers who did what visionary leaders always do—scan a circumstance, find it lacking, and respond with bold, relevant, and important solutions.

It is a story about America, too—even though Johnson does not address the backstory in his book, which I will do here.

In the Republic’s early days, public higher education was reserved for elite White men, the sons of professionals and ministers, who would become the next generation of men with standing and influence, including physicians, attorneys, merchants, those in the arts, politicians, and clergymen.

Women, on the other hand, had limited educational opportunities–even those from affluent families. They could enroll at a limited number of private co-ed institutions (e.g., Oberlin College in Ohio, which admitted African Americans, too) and several private all-women’s schools (e.g., Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts). But public higher education was a different story. No American public university admitted women until the University of Iowa did in 1860 (policy approved in 1857).

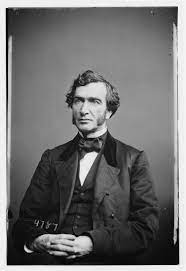

In response to exclusivity, the U.S. Congress aimed to democratize public higher education by making it more accessible to everyday men and women, and legislators acted during America’s Civil War, no less. The Land-Grant Act of 1862, commonly known as The Morrill Act (named after Vermont U.S. senator Justin Morrill), enabled states to sell public land and use the proceeds to launch state-based colleges in the agriculture and mechanical arts.

Senator Justin S. Morrill (R-VT) (photo, Library of Congress)

Land-grant colleges were “every person” schools, open to young men and women who were denied access previously, and the schools focused on agriculture, home economics (for women), and “the mechanical arts.” Early land-grant schools carried the names of those fields in their titles. For example, Pennsylvania selected the Agricultural College of Pennsylvania (now Penn State] to be the state’s land-grant college, and a similar school appellation in Kansas later became Kansas State College of Agriculture and Applied Science (now Kansas State).

But “democratizing” had limited reference in 1862, and not all young people (namely, people of color) could take advantage of what the Act of 1962 offered. Enter the U.S. Congress again, this time in 1890, to address the issue of access for African Americans. But accomplishing that goal was anything but straightforward.

When the Federal government required public state universities to admit Black citizens, Southern states balked at the mandate. Rather than integrate the existing set of land-grant schools, a parallel set emerged in states across the South and Southwest. One set was state-funded for White residents, and the other was Federally-funded for African Americans. So, by the century’s end, South Carolina had Clemson and South Carolina State, Kentucky offered the University of Kentucky and Kentucky State, and Missouri had the University of Missouri and Lincoln University.

Known as “The Second Morrill Act,” the so-called “1890 schools” included 19 schools across 18 states—18 public institutions and one private school (Tuskegee Institute in Alabama). The 1890 public institutions included Florida A&M (launched as the State Normal and Industrial School for Colored People), North Carolina A&T, Alcorn State (Mississippi), Delaware State, Langston University (Oklahoma), the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore (as it is known today), and one school located in the North, Central State (Ohio). Today, those 19 institutions are part of a much larger and broader network of over 100 schools, including Jackson State in Mississippi and Hampton Institute in Virginia, under the rubric of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU).

Mary McLeod Bethune (photo, National Museum of African American History & Culture, Smithsonian Institution)

Stories about the founding of 17 schools are what Johnson tells in his book. Johnson aims to educate and inspire young people using a personality-driven approach, providing background about HBCU founders, including Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune (Bethune-Cookman University), General Oliver Otis Howard (Howard University). Reverand Littleton F. Morgan (Morgan State University), Elijah J. Shaw (Shaw University), and Laura Spelman Rockefeller (Spelman College).

The refreshing thing about the book is that it is about as far away as you can get from the chest-beating branding so frequently associated with today’s higher education (e.g., “We Are Penn State!”). Instead of selling a brand, Johnson sells legacies, focusing on the leaders and leadership that make a public education movement possible.

Each vignette is told differently, some expressed in “back in the day” form and others presented in a contemporary setting. But all the stories share a common theme—who, how, and when these historically Black schools came to be. Even adults familiar with HBCUs can learn new things, sometimes surprising things, such as General Howard was not an African American.

These are institutional legacies for sure, but they are (as the book title states) living legacies—enterprises not only to be cherished and honored but also to be protected and advanced. The message? We should not forge our future without first understanding our past.

Samuel H. Johnson

We should also not celebrate a book without acknowledging who wrote it. Samuel H. Johnson is a Renaissance person who epitomizes what it means to be generative in career and avocational contributions. A graduate of Miami University (OH), Johnson was a U.S. Census Bureau staff member who authored multiple diversity-focused pamphlets (printed in the millions) under the “WE” heading (e.g., We, The Women of the United States). He also has experience in front of and behind the camera. Johnson has appeared in Hollywood films (e.g., G.I. Jane, Runaway Bride) and was an Emmy-winning public television producer at WETA-TV in Washington, DC (e.g., Housing in Anacostia, Seven Years After the Riots). Johnson also did PR work in the District for advocacy and nonprofit organizations (e.g., NAACP, Allen Chapel AME Church). Nimble with the written word, Johnson has written sports articles (e.g., 79 Years Ago I Listened To “The Fight” (Joe Louis v. Max Schmeling), and he is the author of multiple historical novels/novellas and children’s books (e.g., The Cherokee and the Slave).

But perhaps the fascinating item is what Samuel H. Johnson is not–an HBCU graduate—which makes the contribution special. What HBCUs are, who founded them, and how they connect to Johnson’s commitment and passion to keep them in the limelight. He is also engaged in a campaign—to ensure that young people know about HBCUs and why they are important. “After you graduate from high school, you may attend one of the nation’s HBCUs,” Johnson writes at the beginning of his book. “This collection may help you make that choice.”

While it is too late for this author to make that choice, Johnson gave me another gift—that pep talk I needed.

__________

Cover photo courtesy of HBCU Lifestyle

What a lesson, Frank.