By Dr. Glenn Sterner, The Pennsylvania State University.

“Put that stuff at the bottom of your CV, no one really cares about it anyway.”

This was the advice I received from a senior faculty member in my field as we reviewed my engagement activities on my curriculum vitae. For those of us junior scholars and faculty members, especially those in the throes of the academic job market, we seek all the advice we can receive from those more seasoned faculty members in our fields. This advice is supposed to help us land on-campus interviews and, if you are lucky, a coveted tenure-track faculty position.

My academic field is criminology, and, one can argue, an incredibly applied discipline. We address and research pertinent issues associated with the safety of our communities and society more broadly. In this field, one would assume that engagement with communities and the sharing of knowledge produced in our research would be of tantamount interest to our colleagues and institutions. Instead, it seems as though this discipline fits within the dominant paradigm that publishing and granting makes an attractive academic; engagement if you wish.

I share this anecdote not to produce another lament by a junior scholar on the state of engagement in higher education, the priorities of the professoriate, or the need for a reconsideration of the tenure process. Instead, I am curious as to why this advice, that is a consistent message within faculties, is so at odds with institutional rhetoric on engagement – that as an institution, Penn State (and other similar institutions) is dedicated to providing “unparalleled access to education and public service to support the citizens of the Commonwealth and beyond.”

These outward-facing statements our institutions provide to our stakeholders would indicate that we should see alignment across all areas within our organizations with regards to the prioritization of engaging with the public and providing service to address public issues. Who benefits from this external engagement rhetoric by our institutions? Before we explore this question, perhaps it is best to examine the journey of engagement within higher education. (Note: I highly suggest these books by Slaughter and Roades and Thelin, as well as Saltmarsh and Hartley’s chapter in Publicly Engaged Scholars.)

As we explore engagement in early American higher education, we see a preponderance of individuals who may be considered public intellectuals; elite scholars who insert themselves into public life and issues based upon their areas of expertise. As we move into the mid-to-the-late 1800s, we begin to see a shift in the public sentiment toward higher education, recognizing the contributions to society greater access to advanced learning and training can have for the country, noted by the Morrill Acts.

As colleges and universities continued to propagate across the country, this notion of increasing access to knowledge production for the public good continues to be advanced by the development and utilization of cooperative extension in the early 1900s. However, during the Post-World War II and Cold War Eras, higher education and knowledge production began to see a distinct movement from emphasizing sharing and addressing public needs to a commodification of knowledge through a shift towards corporatization and neo-liberal approaches to higher education.

From this lack of responsiveness to public issues rises what we could consider the beginning of the engagement movement in the late 60s and early 70s, where scholars within the academy recognize the need to connect with communities to develop relevant and meaningful relationships with the public and public issues.

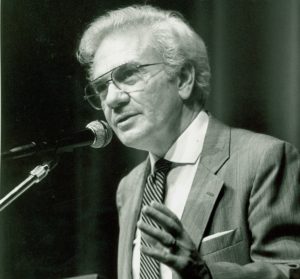

The late Ernest Boyer, father of today’s engagement movement in American higher education (photo, The Carnegie Foundation)

As this movement gains momentum, we see the work of Boyer and reports from organizations like the Kellogg Commission gain greater recognition within higher education more broadly. Yet, even to this day, while we see greater support within higher education for public engagement, there remains a tension between specialized, disciplinary knowledge versus knowledge that focuses on the public good. Within this tension, the former emphasizes addressing disciplinary interests with an agenda largely set by scholars within that discipline, whereas the latter explores issues salient to public issues and the direction is shaped by the public and scholars together.

However, I would like to back up to the 1990s and the efforts of Boyer and the like. It is during this time that support for higher education begins to lag (for which I do not believe we have yet recovered), evidenced not just in public sentiment, but also in appropriations by state and federal governments.

Higher education became to be seen as a private good, serving its own interests and individuals seeking their own advancement, lacking in relevance to the public; frankly, a fair assessment. Boyer and other scholars saw engagement as a way to help academe regain relevance in society once again. And this motivation, though well-intentioned, is highly reactionary and self-serving. In some regards, this rationale for the need for engagement within higher education typifies what John Creighton and Richard Harwood call the “organization-first approach.”

This approach is similar to a friend that seeks out your assistance in times of need but rarely returns the favor. Over time, you begin to realize that when this individual reaches out, likely it is for selfish needs, even though they may mask their requests. In a similar vein, the organization first approach is a strategy that is used to protect the organization, engaging with opportunities only when it benefits the organization. Ironically, this organization-first approach leads not to advancement, but to a weakening of its relevance, for just as we might avoid our insincere friend, so too do others avoid doing business with the selfish organization.

This returns me to my initial motivation for exploring the lack of alignment between disciplinary and institutional messages on engagement – understanding “who benefits?” In this case, when we utilize engagement as a way to emphasize benefit toward higher education, these public facing statements toward community commitments from our institutions become hypocritical.

However, while it took time for this message of engagement’s importance to take hold within and across institutions, it is in response to this message, this opportunity to focus on the needs of the institution, that I consider the beginning of the commodification of engagement.

As higher education administration began to see engagement as a way to reclaim public support, this emphasis on introducing engagement language in the externally facing messages to the public became more prominent. In this way, the institution could gain benefit by focusing on engagement as a tool to advance its own interests, co-opting the engagement movement’s genuine interest in public connections.

Indeed, we see this commodification in the use of revenue generation and mutually beneficial language in engagement strategies, even in recent publications mutually-beneficial engagement remains a central aspect of new engagement recommendations (see Fitzgerald et al., 2016). To note, I do not believe that all engagement efforts or scholars are motivated by selfish interests; most of us doing the work of engagement know that this is hard, labor-intensive, yet rewarding work.

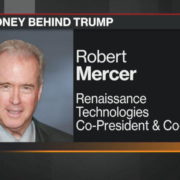

Hunter Rawlings, former president of the American Association, of Universities, believes it’s a mistake to view colleges as commodities (photo, Cornell Chronicle)

Likely this approach is where a portion of the disconnect between disciplinary lack of emphasis on engagement and institutional language on engagement originates. Commodified engagement has the potential to generate revenue and public support for an institution. However, disciplinary advancement and specialized knowledge creation remain contingent upon specialized grant programs and academic publications. Here we begin to see that understanding who benefits helps us to understand the disconnect between disciplinary advice and institutional public language regarding engagement.

Yet, there is a growing discontent at the fringes of engagement with the status quo, just as the engagement movement began at the fringes of higher education. This discontent is developing a new kind of engagement that is not motivated to connect with the public and public issues for the benefit of higher education or their disciplinary advancement, but, instead, because they recognize it is simply the right thing to do.

These Public Scholars are motivated by utilizing their technical knowledge in conjunction with local and indigenous knowledge to identify and address public issues while ensuring knowledge is shared and accessible (both in terms of availability and language). There are individuals within engagement who have been writing about this more authentic engagement for years (Frank Fear, Ted Alter, Scott Peters, John Saltmarsh, Matthew Hartley, among many others), and we are noting a growing number initiatives like Future U, or the initiative I am engaged in with my colleagues in the Philadelphia region known as the Consortium for Public Scholars.

These efforts seek to seamlessly integrate engagement efforts and disciplinary work, binding together across disciplines utilizing public scholarship as a framework. However, as we individual scholars seek to highlight our public scholarship, we must resist the temptation to emphasize this work on our CVs for our own personal advancement. Unlike higher education and engagement, we must resist a scholar-first approach.

Rather, public scholarship should be evident in our methods, engagement, and teaching, and this will be apparent in the products of our work. For those engaged in public scholarship, the question “who benefits?” should be irrelevant; our work should benefit everyone.