Written by Frank A. Fear, MSU professor emeritus.

“What should we do now?” a Michigan State University faculty member asked a few days ago amid upheaval that has characterized the East Lansing campus. While no single path is an elixir, I said, one untraveled path seems definitely worth taking—a faculty and student revolt against higher education’s Administrative Class. “Let’s take back the university from the grip of those who undermine and subvert it,” I said.

“What do you mean?” she asked. I answered by telling two personal stories.

Story 1: Years ago—nearly a half-century ago, truth be told—I announced to friends that I wanted to be a college professor. My friends looked puzzled and for good reason, too. None of them was so inclined and nobody in our immediate families had gone to college, let alone made academics a career.

My audacious declaration became reality, but that’s not the most important part of the story. Even before embarking on my sojourn in the Academy, I knew that it wouldn’t be a job or even a career. It was my vocation, something I was called to do. I didn’t have a clue why. I still don’t. And when it came to administration, I liked to tell people that “I was a professor who happened to be an administrator.” It wasn’t a career path to something ‘bigger and better.’ I already had that. I was a professor.

Story 2: Decades later I was in a conversation very much like the one I just described—except, this time, somebody else was the protagonist. Over drinks one evening I asked a colleague about his long-term plans. “I want to be a college president,” he said without hesitating.

I thought he was kidding. He didn’t have a disciplinary or professional degree and had no intention of earning one, either. He had no desire to teach, research, advise students or do any of the other things that faculty do. His plan was to work in non-academic institutional support roles—alumni affairs and fundraising, among other areas—and establish a reputation that way. He’d move up the system into executive management positions and, then, compete for a presidency. “You don’t need to be an academic these days to be president,” he said that night.

He was right. Today he’s living his dream. Many others are doing the very same thing. They are part of what I call The Administrative Class in higher education. The Academy is full of chief executives who’ve never lived the faculty life.

They don’t know what it’s like to be up at 2 a.m. grading papers or working on a grant proposal. They’ve never experienced department and university service commitments that keep them from getting “that manuscript” edited and submitted. They have no clue what it’s like to look a graduate student in the eye and say, “You’ve failed your comprehensive exam.” They haven’t had long talks with faculty colleagues about what to include in a core course or how to “reach” undergraduate students who seem unreachable.

Because they’ve never experienced any of those—and so many other—things associated with the faculty life, they have no frame of reference for the guts of what they’re administering. They’re in the Academy, but not of it.

Let’s face it, though, these folks didn’t get into authority positions by fiat. They were invited by enablers. I’m talking about governing boards, “trustees,” many of whom prefer to look at higher education as a business, even though some don’t seem to fully comprehend the business higher education is in.

And there’s a big reason why so many politicians and businesspersons serve as college/university presidents and chancellors. In background and approach, they’re just like the trustees who hire them.

For at least a generation, faculty colleagues have complained about this and a whole lot more. And, yes, sometimes complaints are heard. Change happens. But change can also have a mollifying effect. Before long there’s a reset. “Normalcy” returns.

“Yeah, that happened here,” my colleague replied. Shared concerns motivated Michigan State faculty to organize in 2004-05 in an effort with eponymous name, “Faculty Voice.” Important recommendations were made and some were followed, too. But it wasn’t long before there was a reset. Trustees named a president without conducting a national search or holding a public review. The Administrative Class had prevailed.

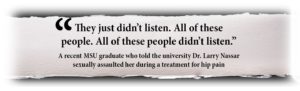

Now the MSU faculty is back at it again. This time, students and staff are very much involved, too. The country knows why. The only question is whether, this time, the grassroots will prevail.

It won’t if this is an interlude in the prevailing routine of business as usual. That’s why it’s time to demand and work toward big, sustained change. Doing that won’t be easy, though. We’re accustomed to “leaving the running of things to others,” even though we always carp about what that option brings (e.g., the plight of adjunct faculty). So we accept the status quo until something “comes up” to really agitate us. We respond, at least for a while, but then return “to our work.”

We fail to appreciate that leading the Academy IS our work—from reforming governance (both administrative and academic), to revamping academic structures and processes, to deciding who will be hired in executive administrative positions and—very importantly—why.

“There was a time at MSU,” I told my younger colleague, “when faculty confronted The Administrative Class.” “When was that?” she asked.

“There’s no better example,” I said, “than Professor Charles P. “Lash” Larrowe.” Larrowe arrived on campus in 1956 and became a popular figure on campus during the 1970s. Among other things, he wrote a column for the student newspaper, The State News, where he took on issues and people of the day—agitating like hell for what he thought was good and proper—on-campus and off-. His pointed critiques, written in bombastic, hyperbolic style, were full of satire and cynicism. People read him and responded.

Lash especially prided himself in calling out the MSU administration. He confronted then-president, the legendary John Hannah, for whom MSU’s administration building is now named. One of Larrowe’s friends, advocates, and mentors was another campus activist, Walter Adams, who at one point (in something that wouldn’t likely happen today) served as MSU’s acting president.

“We don’t have faculty like Larrowe today,” my friend said. She’s right, but faculty engagement doesn’t require bombast. “It just needs the kind of sustained presence we had back then with Larrowe, Adams, and others,” I offered. “People like that could help us achieve another kind of reset—the one I prefer—a paradigm shift in higher education’s executive leadership and governance.”

“And who knows?” she said, “If we stick at it, we might even save ourselves.”

Then my colleague was off to attend a campus rally. Protesters were gathering to decry the Board’s appointment of a politician as MSU’s interim president—an appointment made without consultation and transparency. The Administrative Class was trying to prevail … again.

A few days later my colleague announced that faculty leaders were organizing to seek faculty input on a no-confidence vote in the Board. Not long after she told me it had passed – with nearly 90% of those voting saying a motion should go forward. Academic Governance will take the next steps.

“It’s an important next step,” I told my colleague. “More of the same is needed. Big time. Now.”

“Lash” Larrowe would be proud.