Paul A Miller played various roles in a career that spanned over 70 years, including County Extension agent, faculty member & Extension Specialist, Extension Director, provost, president, and Federal undersecretary, all with the goal of serving the public good. What Paul Miller believed in, stood for, and practiced, will never — and should never — go out of style.

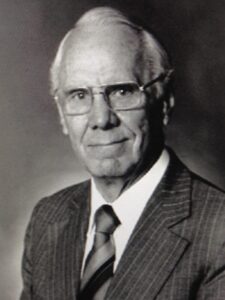

Dr. Paul Ausborn Miller passed away six years ago last week at the age of 98 years. An icon of higher education, Miller’s life is testimony to good things that happen when a person comes from humble beginnings, devotes his life to the public good, and applies that perspective in institutional leadership roles.

Miller is best known for serving as president of two universities—West Virginia University, his alma mater, and Rochester Institute of Technology. But how Miller migrated to university presidencies is arguably the most important storyline of his biography.

Born one hundred and four years ago in East Liverpool, Ohio—an Ohio River town that borders Pennsylvania and West Virginia—Paul Miller grew up on a small farm across the river in Hancock County, West Virginia. Influenced by what he experienced in farm life and what he learned in 4-H, Miller decided that he would make agriculture the focus of his career.

But Miller would not do it as a farmer. Instead, he sought to serve farmers through higher education … with a twist. Unlike many others at the time and since—colleagues who studied various aspects of production agriculture and then became professors of crops, animal science, forestry, and the like—Miller decided to contribute as a rural sociologist.

After graduating from WVU in 1939, Miller worked as an agricultural extension agent in two West Virginia counties—Ritchie (Harrisville) and Nicholas (Summersville)–before joining the war effort as a navigator from 1942-45. After the war, Miller decided to pursue graduate study at Michigan State University, where he studied under major academic figures of the day, including J. Allan Beegle, a noted social demographer. Miller earned master’s and doctoral degrees in East Lansing and was invited to join the faculty.

His tenure at Michigan State spanned a decade. It began as a scholar and MSU’s first extension specialist in rural sociology. He was then appointed director of Michigan’s Cooperative Extension Service, vice-president for off-campus education, and, finally, as the first person to hold the title of ‘university provost’ (vice president of university-wide academic affairs).

Along the way, Miller earned a reputation for being bright, hard-working, dedicated, productive, and collaborative. As one colleague remarked decades later, Miller “had the ability to get along with everybody and to work with everybody.”

Miller’s background and personal characteristics made him a prime candidate to become a university president—and that is exactly what happened. In 1962, Miller returned to Morgantown as WVU president. There, he was especially interested in accentuating the university’s land-grant mission of serving the state’s people.

To do that, Miller believed Extension needed to span the breadth of the university and extend beyond what it had been traditionally—an agriculture and youth development program. And that is exactly what Miller set in motion.

[beautifulquote align=”full” cite=””]“I felt Extension was so powerful that it needed to come out of that narrowly defined role and become an arm of the whole university,” Paul A. Miller[/beautifulquote]

That contribution is acknowledged today by WVU’s current president. E. Gordon Gee, who called Miller’s vision ‘a powerful legacy’ because it laid the foundation for “redefining WVU’s engagement in the 21st Century with the people of West Virginia.”

Washington, DC took note of Miller’s success in Morgantown, and, in 1966, President Lyndon Johnson appointed him as the first Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. There, Miller continued his quest to serve the public good. Among other things, he helped establish The National Technical Institute for the Deaf, which was the world’s first academic center to address the needs of deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Today, it is the world’s largest.

With the idea that the Institute would be housed on a college campus, Miller oversaw a proposal review process, and submissions rolled in from major universities around the country, including Pennsylvania State University and the University of Southern California. Rochester Institute of Technology was selected as the winner and, three years later, Miller was appointed RIT’s president, a post he held for a decade.

[beautifulquote align=”full” cite=””]While vision had become Miller’s trademark up to that point in his career, it was administrative acumen that would define his tenure in Rochester. That is because he inherited a set of challenges that required the response of a skillful, experienced administrator.[/beautifulquote] There was a budget deficit, lagging faculty salaries, declining student enrollment, and other issues that could only be defined as ‘problems.’

Miller met all challenges head-on and achieved success in the process. Most notably, RIT’s enrollment almost doubled during Miller’s presidency—an outcome that was largely the result of adding 70-plus academic options. Amazingly, more than half of the students enrolled at RIT in 1977 were in programs that had not existed five years earlier.

A hallmark of RIT education is cooperative education, an approach that connects the academic world and employment. Here you can watch Miller (and other RIT presidents) talk about its importance.

After leaving RIT, Miller served in various volunteer roles and was appointed to a variety of boards and directorships, including at nearby Nazareth College in Pittsford, NY. He ended his long career by teaching at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and authoring a memoir, Bridging Campus and Community, which was published in Miller’s 97th year. The book’s theme is the theme of his life, namely, “a steadfast commitment to education as the foundation for both individual and democratic progress.”

[beautifulquote align=”full” cite=””]“Two clusters of values overlap in the American psyche. On one side are those that see the citizen as the bearer of individual rights, and on the other is the sharing of life’s commitments and common visions and plans for the future. The central question is how shall we best live our lives together?” Paul A. Miller, from his article in Adult Education Quarterly, 1995[/beautifulquote]

On June 5, 2015, Paul A. Miller passed away at his retirement home in Montrose, Colorado. He was preceded in death by his first spouse, Catherine Spiker Miller (1964), their one-day-old daughter and son, Kay and Gay, son Thomas, and Paul’s second spouse, Francena Miller (2010). Francena, also a rural sociologist, was Paul’s writing collaborator and partner on various philanthropic endeavors, including WVU’s Paul A. and Francena L. Miller Presidential Scholarship.

Paul Miller is survived by Paula Miller Nolan, his daughter with Catherine, her husband, and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

There many interpretations of what it means to be ‘a great leader’ and how higher education is best served by those who have responsibility for its stewardship. But what Paul believed in, stood for, and practiced will never (and should never) go out of style. In fact, we need all of that today perhaps more than we did during his lifetime.

[beautifulquote align=”full” cite=””]“Whatever universities do in the years ahead will likely show in in the kind of society attempted or achieved by the people whose lives they touched.” Paul A. Miller in his address, “University in the Post-Modern Community,” East Lansing, MI, February 1960[/beautifulquote]

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I followed Paul Miller, literally, throughout my career. Also a rural sociologist, I did my undergraduate work at St. John Fisher College, Rochester, NY, when Paul served as RIT’s president. I completed a master’s degree at WVU. Earlier, Paul completed his undergraduate work there and, later, served as its president. My academic/administrative career was spent at Michigan State, where Paul received his graduate degrees and played various academic/administrative roles, including provost.

Thank you, Frank, for this fine remembrance. What a remarkable career of leadership, and life well lived. It makes me wish that I had known Dr. Miller. Thanks again.

I believe a more thorough biography of Paul A. Miller should have garnished his collaboration with Theodore Hesburgh and Clifton Wharton, Jr. in Implementing a “Learning Society”, publicized in Patterns in Lifelong Learning. The paradigms in this publication is replete with antithetical concepts of what is normally viewed as education in America. The authors knew that implementing a Learning Society would be “as difficult as turning the Ten Commandments upside down”. (pg. 52) It meant changing American school structure, policy, process, teaching methods, This book was the culmination of outcomes by 6 taskforces, put together in 3 parts, wrapped in an eerie jacket and duly sent to the press. The authors spoke of ‘relaxing the curriculum’ and reducing the numbers of college bound students. Teachers are to be ‘facilitators’ and students are to construct knowledge. Engineering studies would be slanted toward “ecological control”. Miller’s regional education laboratories suffocated excellence in education, stealing millions of dollars over the decades to dummy down America’s children.

Diana Anderson – researcher and author.

Thank you for posting this. Paul Miller was my Uncle and I am very proud of him. His first wife was my dad’s sister. He was a very successful man but never put on airs or thought he was better than anyone else. My fondest memory of him was me teaching him how to throw a boomerang in my parents yard. It’s hard to imagine someone so educated, influential, and important taking the time to learn something like that but he seemed genuinely interested. His children Paula and Tom where the same way. I miss talking to him at the Spiker Family Reunions. He is buried next to my Parents at South Fork Cemetery in Ritchie Co. WV.